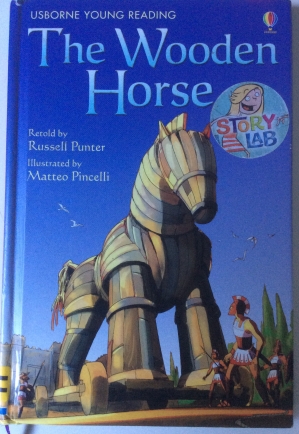

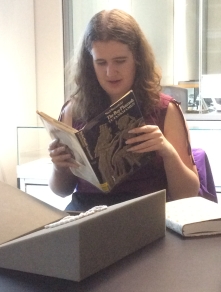

My previous blog posts have shared the experience of attending the Our Mythical Childhood show and tell at the University of Roehampton, but whilst I talked about other people’s contributions I didn’t discuss mine. The book I chose to share with everyone was The Wooden Horse retold by Russell Punter, and illustrated by Matteo Pincelli. It is an Usborne Young Reading (series 1) book, and was first published in 2011. Unlike some of the contributors to the event, this book was not one from my childhood, I had only come across it about about a year ago when I had started looking at Helen of Troy in comics, graphic novels, and children’s illustrated/picture books.

My previous blog posts have shared the experience of attending the Our Mythical Childhood show and tell at the University of Roehampton, but whilst I talked about other people’s contributions I didn’t discuss mine. The book I chose to share with everyone was The Wooden Horse retold by Russell Punter, and illustrated by Matteo Pincelli. It is an Usborne Young Reading (series 1) book, and was first published in 2011. Unlike some of the contributors to the event, this book was not one from my childhood, I had only come across it about about a year ago when I had started looking at Helen of Troy in comics, graphic novels, and children’s illustrated/picture books.

It is a very simplified version of the story, but what I like (in books like this one) is how the author has to make certain choices and decisions about which bits of myths to use, and how best to distil the essence of the story, and in doing so decide what aspect they are going to portray.

Although this book is about the Wooden Horse, to give context the narrative is framed by Helen’s story. Within the book there are only five named characters – Helen, Menelaus, Paris, Odysseus and Sinon. The book begins with Helen – her name is actually the first word in the story, and ends with her being taken back to Sparta. She is a very passive character, and the only time she is given a voice it is internal, when she thinks about what will happen when Menelaus reclaims her. Despite this being a very simple version we can see how she is portrayed very much as an object – Menelaus is ‘proud’ of having a ‘lovely wife’, and we see her as a possession of his. Once Troy has been defeated Helen is taken back alongside Trojan treasure – the implication being that she too is a piece of ‘treasure’, an object to be shipped back. Probably the most interesting sentence in the book (for me), occurs on the final page : “Helen may not have wanted to go back to Greece, but she had no choice.” (p. 47) Which speaks volumes.

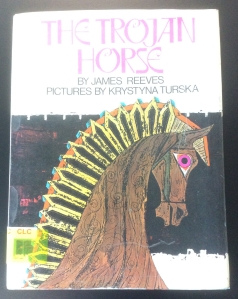

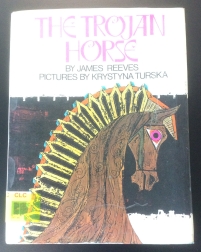

In the afternoon of the ‘show & tell’ we chose books from the University of Roehampton’s special collections and, as I told in a previous post, I picked a book called The Trojan Horse, by James Reeves and illustrated by Krystyna Turska as I thought it would prove to be an ideal counter part to the book I had brought with me. The episode of the wooden horse is framed in quite a different way and is told through the character of Ilias, a grown man (at the time of telling) but who was aged ten when Troy fell. He and his younger sister, Ida, escaped and now live far from their ruined former home. In The Wooden Horse Paris and Helen fell in love, but in this version Ilias describes how Paris stole Helen and kept her prisoner in Troy. Most of the war is glossed over, and it is really only the episode of how the horse appeared and was brought into Troy and the terrible consequences, that is told. It is Ilias’ life that frames the episode rather than Helen’s and we are given an insider’s view on events. As mentioned above I enjoy seeing how writers will encapsulate a particular myth, and particularly liked how these two books, which on the outside might lead one to thinking they would be similar, provide very different aspects of the story. Incidentally neither of them include the episode related in The Odyssey (IV: 265-289) about Helen calling out to men within the horse using the voices of their wives.

In the afternoon of the ‘show & tell’ we chose books from the University of Roehampton’s special collections and, as I told in a previous post, I picked a book called The Trojan Horse, by James Reeves and illustrated by Krystyna Turska as I thought it would prove to be an ideal counter part to the book I had brought with me. The episode of the wooden horse is framed in quite a different way and is told through the character of Ilias, a grown man (at the time of telling) but who was aged ten when Troy fell. He and his younger sister, Ida, escaped and now live far from their ruined former home. In The Wooden Horse Paris and Helen fell in love, but in this version Ilias describes how Paris stole Helen and kept her prisoner in Troy. Most of the war is glossed over, and it is really only the episode of how the horse appeared and was brought into Troy and the terrible consequences, that is told. It is Ilias’ life that frames the episode rather than Helen’s and we are given an insider’s view on events. As mentioned above I enjoy seeing how writers will encapsulate a particular myth, and particularly liked how these two books, which on the outside might lead one to thinking they would be similar, provide very different aspects of the story. Incidentally neither of them include the episode related in The Odyssey (IV: 265-289) about Helen calling out to men within the horse using the voices of their wives.

Whilst many of the contributor’s shared books or items that they remembered being influences from their childhood, I realised that I don’t actually recall any particular book with a classical theme from when I was a child. I feel a bit bereft! I’m sure there must have been books on mythology, but I can’t pinpoint when my interest in the classical world began to emerge. What I do remember well was in sixth form we were allowed to take Classical Studies (which we couldn’t do before then), so in the lower sixth we did the O level, and in the upper sixth the A level (only one year each). We had the most wonderful teacher, Mrs Janet Cox, whom I found very inspiring. I had obviously discovered the classical world before this point, but this was where I really started learning about it. Having a teacher who loved her subject made it come alive for all of us. She would also play music and bring in biscuits for us at break time, and there were classically themed posters on the walls of the classroom.

Incidentally, I also remember that she kept bees in her garden, and it is because of her that I joined The Green Party when still a teenager!

She taught Latin to a mere handful of students at lunchtimes (when I was doing O levels), sadly I never took this option! It was probably not suggested to me as I wasn’t particularly good at French (the one language we all had to do), and at the time it never really occurred to me to request joining the class. Grown up Karen is very sad that teenage Karen did not do this!!!!

I enjoyed the ‘show & tell’ and having the opportunity to hear about other people’s formative experiences and books, and have also relished having the opportunity to reflect on my own journey within Classics. I am also keenly looking out for children’s books that retell Helen’s story, and also that of the Trojan Horse.

As a librarian I was also impressed by the lovely electric rolling stacks, operated by a touch screen, and moving quietly and smoothly without the aid of human arm power! (and quite unlike the electric powered ones I used to have to use in the UWCM medical library which were quite monstrous in construction (think Frankensteinian levers), and so terrifying to use that most students didn’t dare!). But I digress…

As a librarian I was also impressed by the lovely electric rolling stacks, operated by a touch screen, and moving quietly and smoothly without the aid of human arm power! (and quite unlike the electric powered ones I used to have to use in the UWCM medical library which were quite monstrous in construction (think Frankensteinian levers), and so terrifying to use that most students didn’t dare!). But I digress… I picked The Trojan Horse as it had the same subject (and similar title) as the book I had brought to share, but was a very different interpretation of the story, being told from the viewpoint of a family within Troy, who were suffering due to the Greek attack. Helen was not a focus at all. But I also picked it because of the illustrations which I was really drawn to. Krystyna Turska (1933-), was born in Poland; she spent time in a Russian concentration camp, before coming to England where she established her illustrating career. Her style was perfect for myths and fairytales, and The Trojan Horse was not the only classical based work that she did.

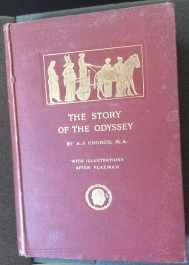

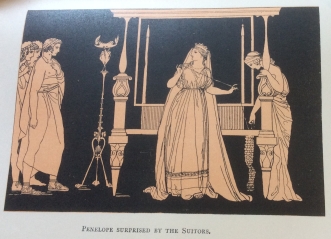

I picked The Trojan Horse as it had the same subject (and similar title) as the book I had brought to share, but was a very different interpretation of the story, being told from the viewpoint of a family within Troy, who were suffering due to the Greek attack. Helen was not a focus at all. But I also picked it because of the illustrations which I was really drawn to. Krystyna Turska (1933-), was born in Poland; she spent time in a Russian concentration camp, before coming to England where she established her illustrating career. Her style was perfect for myths and fairytales, and The Trojan Horse was not the only classical based work that she did. The Story of the Odyssey was also illustrated but the pictures were done in the style of Greek vase paintings and were taken from John Flaxman’s designs.

The Story of the Odyssey was also illustrated but the pictures were done in the style of Greek vase paintings and were taken from John Flaxman’s designs.

Richard had found a copy of The Bronze Sword by Henry Treece (1965), part of a trilogy set in Roman Britian and centered on Boudicca. He had also found copies of Junior Bookshelf, a review periodical founded in 1936, and aimed at teachers and librarians. Richard pulled out the issue which reviewed The Bronze Sword, so we were able to hear how it was positively received. He had also found a review for a Mary Renault book which wasn’t particularly well received, and the issue was raised about ‘gender’, and expectations from male and female authors.

Richard had found a copy of The Bronze Sword by Henry Treece (1965), part of a trilogy set in Roman Britian and centered on Boudicca. He had also found copies of Junior Bookshelf, a review periodical founded in 1936, and aimed at teachers and librarians. Richard pulled out the issue which reviewed The Bronze Sword, so we were able to hear how it was positively received. He had also found a review for a Mary Renault book which wasn’t particularly well received, and the issue was raised about ‘gender’, and expectations from male and female authors. Tony Keen (who joined us for the afternoon session) chose

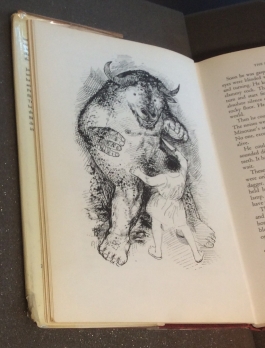

Tony Keen (who joined us for the afternoon session) chose  Nanci had picked The Hamish Hamilton book of Myths & Legends by Jacynth Hope-Simpson (1964), which turned out to also have illustrations by Krystyna Turska, and we all particularly liked the Minotaur who looked quite cuddly really! If I remember correctly we found that Theseus seemed to be exonerated for many actions in this version, in that deeds he is usually acribed – such as abandoning Ariadne – were here blamed on others, such as the fact that it was the sailors who sailed away forgetting her. He was very much being glorified as the hero.

Nanci had picked The Hamish Hamilton book of Myths & Legends by Jacynth Hope-Simpson (1964), which turned out to also have illustrations by Krystyna Turska, and we all particularly liked the Minotaur who looked quite cuddly really! If I remember correctly we found that Theseus seemed to be exonerated for many actions in this version, in that deeds he is usually acribed – such as abandoning Ariadne – were here blamed on others, such as the fact that it was the sailors who sailed away forgetting her. He was very much being glorified as the hero. Robin had veered away from Greek myth and found The Boy Pharaoh: Tutankhamen by Noel Streatfeild (1972). This was a non-fiction book for children, and not something I had been aware of Streatfeild writing, being much more familier with her “shoes” books (e.g. Ballet Shoes).

Robin had veered away from Greek myth and found The Boy Pharaoh: Tutankhamen by Noel Streatfeild (1972). This was a non-fiction book for children, and not something I had been aware of Streatfeild writing, being much more familier with her “shoes” books (e.g. Ballet Shoes).

nant as Dr Who, was set just before the eruption of Mount Vesuvius in AD79. The Dr interacts with Caecilius and members of his family, Metella and Quintus, all based on the CLC characters. Richard noted that the TV series “Plebs” based in ancient Rome has also named some of its characters from those appearing in the CLC. He surmised that writers on both shows probably experienced the CLC when younger, and have brought this cultural influence to their writing. He also noted that the course seems to have inspired a wide culture of response and memory with fan fiction, and YouTube videos for example.

nant as Dr Who, was set just before the eruption of Mount Vesuvius in AD79. The Dr interacts with Caecilius and members of his family, Metella and Quintus, all based on the CLC characters. Richard noted that the TV series “Plebs” based in ancient Rome has also named some of its characters from those appearing in the CLC. He surmised that writers on both shows probably experienced the CLC when younger, and have brought this cultural influence to their writing. He also noted that the course seems to have inspired a wide culture of response and memory with fan fiction, and YouTube videos for example. Anwen Hayward, Phd student, University of Roehampton, brought Realms of Gold: Myths & Legends From Around the World by Ann Pilling (1993). She admitted that as a child she was obessed with Greek myths. The cover of this book is classically themed and gives the impression that that is the main content, when in fact there are myths from Africa, Russia, India, Wales, and Norse legends. Anwen said she remembered being particularly pleased (as Welsh herself) that a Welsh story was included. It was interesting that visually the cover was designed to show classical themes, and perhaps this was a deliberate ploy to attract readers who were already familiar with Greek myths, and then introduce them to other cultures.

Anwen Hayward, Phd student, University of Roehampton, brought Realms of Gold: Myths & Legends From Around the World by Ann Pilling (1993). She admitted that as a child she was obessed with Greek myths. The cover of this book is classically themed and gives the impression that that is the main content, when in fact there are myths from Africa, Russia, India, Wales, and Norse legends. Anwen said she remembered being particularly pleased (as Welsh herself) that a Welsh story was included. It was interesting that visually the cover was designed to show classical themes, and perhaps this was a deliberate ploy to attract readers who were already familiar with Greek myths, and then introduce them to other cultures. Alison Waller, Senior Lecturer in children’s literature, University of Roehampton, brought Crown of Acorns by Catherine Fisher (2010). This book isn’t a classical story, or a retelling of a myth, but does have some classical influence within it. It is based in Bath, and one of the characters calls herself Sulis, her (chosen) name and ideas about identity are tied in with the plot. Alison mentioned the importance of ‘place’ within stories, and the associations that get linked to them. In this instance with Bath there are several different versions that people resonate with – for example, Roman Bath, and Jane Austen’s Bath – two very different cities, but in the same location. This also means that there are a mixture of influences on people reading the book, and in general when we are thinking about place. I’ve only read a couple of Fisher’s books, but will certainly be looking this one up.

Alison Waller, Senior Lecturer in children’s literature, University of Roehampton, brought Crown of Acorns by Catherine Fisher (2010). This book isn’t a classical story, or a retelling of a myth, but does have some classical influence within it. It is based in Bath, and one of the characters calls herself Sulis, her (chosen) name and ideas about identity are tied in with the plot. Alison mentioned the importance of ‘place’ within stories, and the associations that get linked to them. In this instance with Bath there are several different versions that people resonate with – for example, Roman Bath, and Jane Austen’s Bath – two very different cities, but in the same location. This also means that there are a mixture of influences on people reading the book, and in general when we are thinking about place. I’ve only read a couple of Fisher’s books, but will certainly be looking this one up. Next was Nanci Santos, Independent Researcher, who brought some intriguing comic books in Portuguese (but are also available in English), featuring Donald Duck and his Uncle

Next was Nanci Santos, Independent Researcher, who brought some intriguing comic books in Portuguese (but are also available in English), featuring Donald Duck and his Uncle  is sometimes portrayed as an antiquarian, and there have been instances of time travel, such as back to ancient Egypt. This was another example of how classical myth can reach into unexpected places.

is sometimes portrayed as an antiquarian, and there have been instances of time travel, such as back to ancient Egypt. This was another example of how classical myth can reach into unexpected places. Following on was Kimberly MacNeill, PhD student at the University of Roehampton, and her object was a doll, but not any ordinary doll, this was

Following on was Kimberly MacNeill, PhD student at the University of Roehampton, and her object was a doll, but not any ordinary doll, this was  t the doll for her daughter, and her daughter provided a lovely illustration of her doll for us plus a few key thoughts. Kimberly suggested people should perhaps look at their own children to see how they are interacting with the classical world (perhaps they are more heavily influenced if their parents are interested in the classics). You will also notice how children want to question who are the good guys and who the bad, and what they base their decisions on (a smile = good……).

t the doll for her daughter, and her daughter provided a lovely illustration of her doll for us plus a few key thoughts. Kimberly suggested people should perhaps look at their own children to see how they are interacting with the classical world (perhaps they are more heavily influenced if their parents are interested in the classics). You will also notice how children want to question who are the good guys and who the bad, and what they base their decisions on (a smile = good……). Our last contributor for the day was Sara Venkatesu, Ph.D. students, University of Roehampton. She commented about how her childhood had been filled with books, courtsey of her parents. Books were everywhere (which sounds like my house now!), and the book she brought to share with us was Sirene by Helga Di Giuseppe and Felice Senatore (2014). This book tells the story of the Sirens in a very particular way, taking appropriations from Italian myths and stories where the Sirens are portrayed very positively, especially Naples where it is believed that a Siren founded the city. In Italy Sirens are portrayed as calm and gentle creatures, available to help. In this book the Sirens are drawn as beautiful women with the legs of birds; Homer doesn’t describe the physical attributes of the Sirens in much detail, and in some cultures Sirens and Mermaids are interchangeable. Anna noted that in Polish the same word is used for both. Sara also brought another book featuring Sirens – I mitici sei: Il segreto delle sirene (The mythical six: the secret of the sirens) by Simone Frasca and Sara Marconi (2016), part of a children’s book series based on myth and science fiction.

Our last contributor for the day was Sara Venkatesu, Ph.D. students, University of Roehampton. She commented about how her childhood had been filled with books, courtsey of her parents. Books were everywhere (which sounds like my house now!), and the book she brought to share with us was Sirene by Helga Di Giuseppe and Felice Senatore (2014). This book tells the story of the Sirens in a very particular way, taking appropriations from Italian myths and stories where the Sirens are portrayed very positively, especially Naples where it is believed that a Siren founded the city. In Italy Sirens are portrayed as calm and gentle creatures, available to help. In this book the Sirens are drawn as beautiful women with the legs of birds; Homer doesn’t describe the physical attributes of the Sirens in much detail, and in some cultures Sirens and Mermaids are interchangeable. Anna noted that in Polish the same word is used for both. Sara also brought another book featuring Sirens – I mitici sei: Il segreto delle sirene (The mythical six: the secret of the sirens) by Simone Frasca and Sara Marconi (2016), part of a children’s book series based on myth and science fiction.